“Many design traditions are shaped by an ecosystem that goes beyond design,” he continues, “In Germany, design is linked to the steel industry. In France, it has more to do with interior decoration, and therefore to craft. Switzerland lies somehow in between the two worlds: objects are produced with the help of innovative machines and technologies, yet often this is done by companies which are still rather small, with a lot of manual work involved. This intermediary position between engineering thought and high skill in execution is a good recipe for innovation and quality. It’s also a matter of responsibility. In a small country, you cannot fool around.”

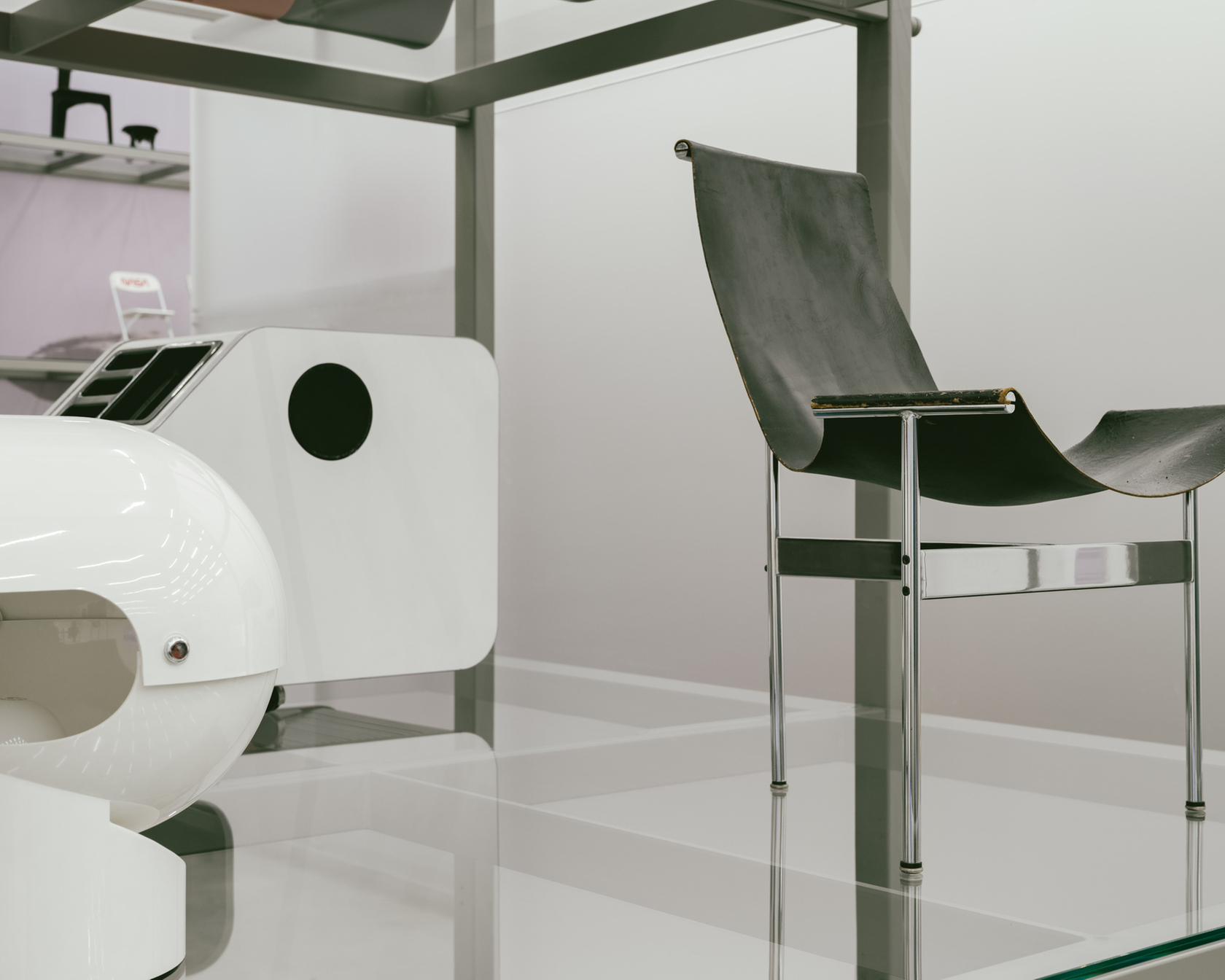

The Fehlbaums know this well. In their steady rise to build one of the world’s most renowned and beloved furniture brands, both for the office and for the home, they never lost a sense of balance and respect for where they were coming from. Today, Vitra has operations all over the world, and still the decisions are taken by a third-generation family member, Raymond’s daughter Nora, from an office situated not far from where the company was founded. This ethos is reflected on the level of independence that the company has always granted the museum. The staff doesn’t have to inform the company about their activities or ask permission to organise a specific exhibition. Still, many Vitra employees visit the shows to take inspiration or use the collection to discover forgotten designs and place them back into production.

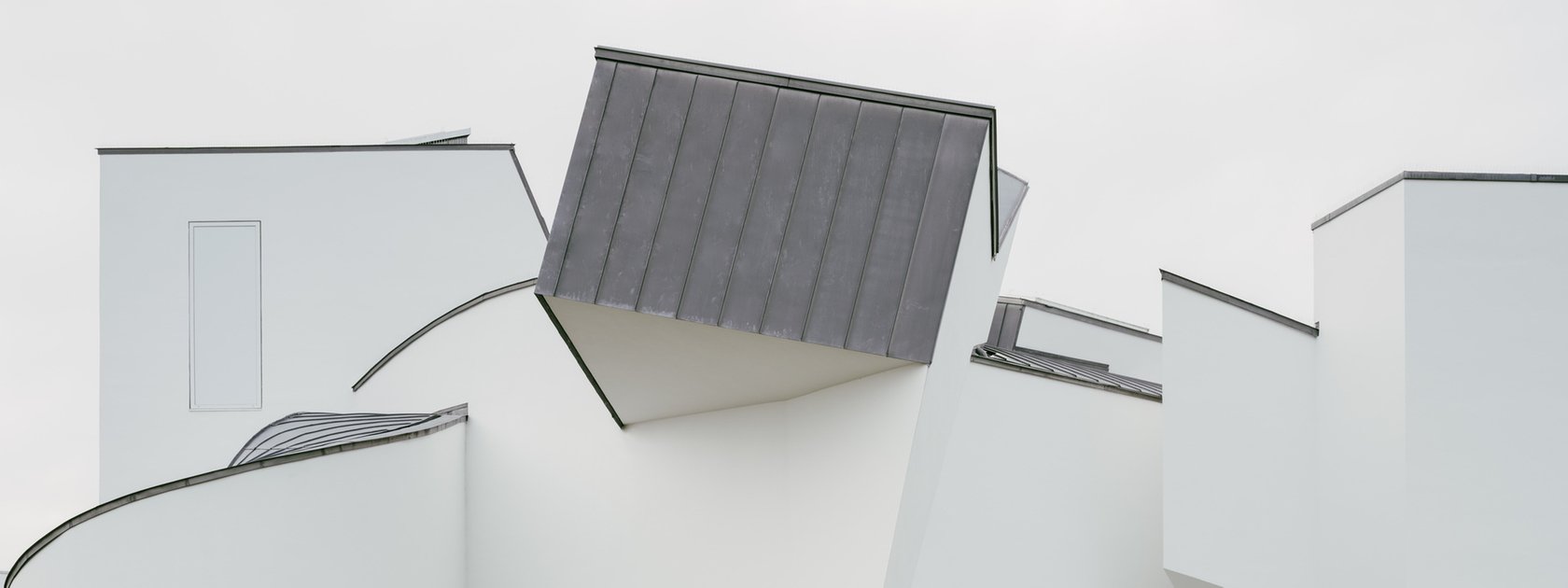

Editorial freedom has allowed the Vitra Design Museum to acquire widespread credibility, interact with public museums and foundations around the world, deal with other corporate sponsors, and ultimately reach a much larger audience. “We think it is good to reach many people and translate questions of design in an understandable language,” Kries says, “We want to be popular in a positive sense.” An example of this attitude is the exhibition that is currently on display inside the Gehry building. Titled Nike. Form Follows Motion, it focuses on the sportswear brand’s design history, from the Swoosh logo to the most iconic sneaker models and the recent research on future materials and sustainability. Next on the program is a show about the Shakers, a religious group operating in the United States since the late 18th century, with exhibition design by the revered contemporary duo Formafantasma.